BYU will honor the Black 14 against Wyoming, but who even are they and why do they matter?

This is not another article about Duke volleyball player Rachel Richardson and the alleged racial slurs that were levied in her direction and later refuted after an investigation determined there was no racial slurs levied. We're not going to talk about that today.

Without making that instance the subject of today's article, we do need to reference it in order to set up today's topic.

Immediately after the claims of racial slurs came out, BYU had to grapple with two different stories. First, they had the story of the fan and the alleged instance(s) of racism in the Smith Fieldhouse during that match. Second, they had to deal with the narrative that was sweeping the nation that BYU had a racism problem. Those stories were two different stories. One of those stories could refuted - or at minimum, subdued - by a thorough investigation of what happened. The other story was bigger than BYU volleyball, BYU athletics, or even BYU the school. The other story has been an ongoing narrative about BYU for decades.

Now, before anyone grabs their pitchforks to tell me I'm wrong and that racism doesn't exist at BYU, let me explain. That explanation goes all the way back to 1968 and BYU football game against Wyoming inside Cougar Stadium in Provo.

--

The Civil Rights Movement was in full swing during the 1960s. Throughout the entire country, race and equality were major topics of discussion.

In 1968, Wyoming's football team travelled to Provo, UT for a game against BYU. During that game, their players alleged that they were treated in despicable manner on and off the field.

Star defensive lineman Tony McGee said that players took cheap shots at his knees and spit on him while he was on the ground. Refs and coaches ignored his complaints and, allegedly, allowed the activity to continue. When the team was walking their way back to the locker room, the sprinklers were turned on and the team was drenched.

"I don't have a problem with Mormons," McGee said to his teammates in 1969. "I have a problem with my treatment on the field."

For others, the protest was about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' policy that prohibited blacks from receiving the Priesthood.

There had been many various protests about the Church's policy throughout the 60s, typically from fans or activist groups boycotting games. The Black Student Alliance, an activist group on campus in Laramie, proposed a similar boycott for the Wyoming vs. BYU football game in 1969. Players rebuffed the proposal, stating that similar protests hadn't led to any meaningful change in the past.

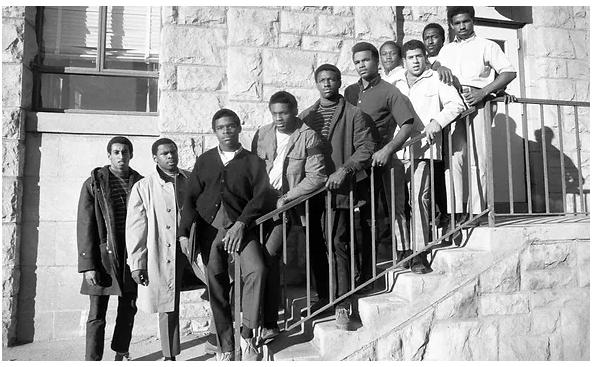

Instead, 14 black players on the team wanted to wear black armbands donning "Black 14" during the game. The idea behind the protest was to signify to BYU players and fans that if anyone messed with one of the black athletes on the team, they were messing with 14 black athletes on the team.

Before staging the protest, the Black 14 (as they later become known) decided to talk to their head coach, Lloyd Eaton.

Eaton was a disciplinarian. He wanted full compliance with his edicts from all players on his team and he wasn't standing for this protest. Instead of allowing his players to say what they had to say, he immediately kicked them off the team.

As the protest plans were being revealed to Eaton, he cut them off. Tony Gibsons recalled the coach's interjection going something like this:

" I can save you a lot of time. As of this moment, you are no longer members of the Wyoming football team."

The irony, as Gibson recalled in 2009, was that had Eaton said no to the armband protest, the Black 14 intended on playing the football game without the armbands. But, Eaton never allowed that conversation to happen.

Other players remembered more specific, and gut-wrenching, statements from Eaton. Jay Berry recalls Eaton saying, "If it weren't for me, you'd all be on negro-relief."

Joe Williams was a team captain at the time. He remember the interaction with his coach going like this.

"He came in, sneered at us and yelled that we were off the squad. He said our very presence defied him. He said he has had some good Neeegro boys. Just like that."

Protests came to Laramie after the Black 14 were kicked off their football team. From that point on, the group became a cause for activism and equal rights. Now, the group continues to work on helping serve underserved communities. Just a few years ago, in conjunction with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, they delivered 800,000 pounds of food to those communities.

The Black 14 sought out to make a statement calling for change. More than 50 years later, they are still a cause for good.

Two of the Black 14 will be honored at LaVell Edwards Stadium on Saturday night.

--

The entire premise of the Black 14 was founded on a Church policy that many felt was discriminatory and racist, and the treatment of minorities on the field in Provo in 1968.

In the 60s, especially in 1968 and 1969, tensions in race relations were incredibly strained. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy - two very prominent figures throughout the Civil Rights movement - had both been assassinated in 1968. This, of course, was after Malcom X had been assassinated in 1965. People were jailed. Integration was being pushed throughout the country and there were protests, violence, and tension throughout the country. The Black Panthers had been formed and were on the rise as a movement in the country.

The entire country was struggling with racial injustices. There was violence and racism throughout the country. We'll never know for sure if Tony McKee's treatment on the field in 1968 was racially driven or if the sprinklers were turned on because there were black players. All we can know is what those players said.

For a lot of people throughout the country, those things that were said and the Church's Priesthood policy at the time are the things that they still think about when they think about BYU. So, when a Duke volleyball player alleged racial slurs from fans, it triggered memories of the Black 14 and their cause. As a result, the story of 'racist BYU' stopped being about Rachel Richardson at all, it was - in the minds of many - a confirmation of things that had subtly been in the back of their minds for decades; BYU is racist.

Going forward, BYU has to address those concerns head on. Disproving the allegations of one alleged racist event doesn't help erase narratives that have been growing for more than five decades. For BYU to shake this narrative in the future, they have to go above and beyond in showing that Provo, UT is a place of belonging and a place of acceptance.

Bringing the Black 14 into Provo all these years later is a great step to take.

For many, it was the Black 14's story that brought race and BYU to the forefront of the conversation. Now, BYU and the Black 14 have a major opportunity; to show that everyone can forgive, can love, and work together for a better future no matter how they found each other in the past.

That, my friends, is the most exciting thing about this football game on Saturday. That, my friends, is something that all of us should be looking forward to.